By Dr Shane Oliver, Chief Economist and Head of Investment Strategy at AMP.

Key points

- The Federal Government’s Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook (MYEFO) saw a slight reduction in projected budget deficits compared to the March Budget.

- The continuing windfall from stronger than expected tax collections saw the forecast budget deficit for this financial year revised down to $36.8bn (from $42.1bn in the Budget) with savings allowing slightly lower deficits forecast for the next three years. However, the budget profile deteriorates again after 2028-29.

- Structural pressures on spending remain for the years ahead and are expected to see spending as a share of GDP remain around 27% of GDP, well up on pre pandemic levels.

- The MYEFO implies continued high levels of government spending and a fiscal easing this financial year as the deficit deteriorates.

- Ongoing high levels of public spending and fiscal easing are contributing to capacity constraints in the economy and higher than otherwise inflation and interest rates.

- The Government needs to further rein in spending and put in place measurable fiscal rules to makes its fiscal strategy clearer.

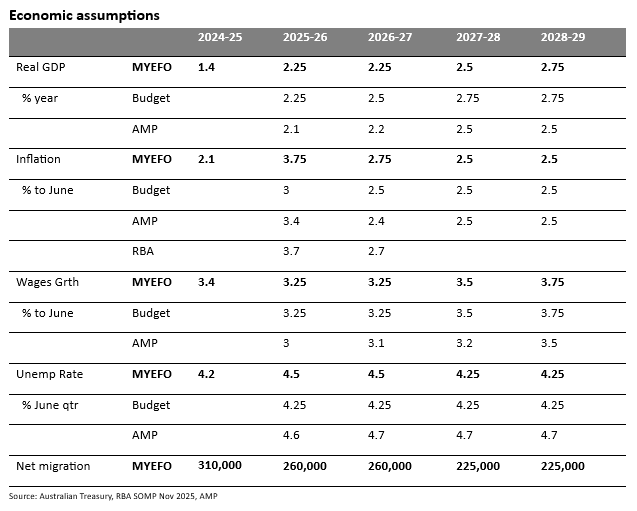

The Government revised up its inflation forecasts for this year but looks more optimistic than the RBA and made little change to its economic growth forecasts.

Growth seen as picking up, but inflation revised up for this year

The Government continues to see growth picking up to around 2.25% with increased confidence in the private sector recovery and stronger business investment. However, its now seeing slightly higher unemployment at 4.5%. And reflecting the reality of recent higher inflation data it revised up its inflation forecasts for this financial year to 3.75%, which is in line with RBA forecasts, and then sees it falling back to 2.75% next financial year and 2.5% thereafter. Note that the upwards revision for this financial year does not reflect the ending of the electricity rebates as they were assumed to end this year back in the March Budget but rather reflects other upwards pressures on prices.

The Government surprisingly lowered its net migration forecast for the last financial year to 310,000 and continues to see a further fall to 225,000 in the years ahead. This is down from a record high of 538,300 in 2022-23. This implies an easing in the underlying demand for housing but with dwelling completions remaining well below the Government’s target for 240,000 a year no significant progress in reducing the housing shortage the accumulated housing shortfall of 200,000 to 300,000 dwellings is likely in the near term.

The deficit outlook is only slightly better than in the Budget

With structural spending pressures intensifying, the cost of existing spending programs continuing to blow out and the good luck – flowing from stronger than expected commodity prices and jobs driving stronger revenue flows to Canberra – getting smaller over time, the mid-year budget update confirms that the budget is moving back into deficit.

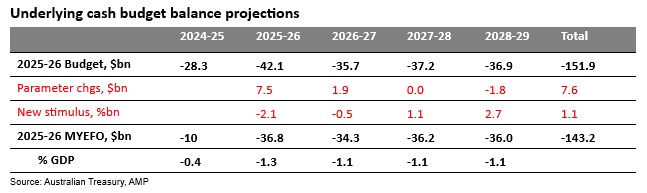

The good news though is that the budget deficit over the next four years is now slightly better than forecast in the March Budget. For this financial year the deficit is now forecast to be lower at $36.8bn, down from the $42.1bn projected in the March Budget – consistent with the better-than-expected monthly profile up to October largely on the back of higher-than-expected commodity prices driving higher than expected corporate tax revenue. Over the forward years its lower in every year but only modestly at about $1bn a year and over the for years to 2028-29 its $8.7bn lower in total.

Put simply while the Government has seen a blowout in spending commitments under existing programs and made some new policy spending decisions this has been more than offset by another round of windfall tax revenue upgrades, particularly in the current financial year, and $20bn in savings over the four years to result in a net reduction in the budget deficit forecasts. The new “savings” of around $20bn over the four years includes a further reduction in the use of consultants, raising the pension deeming rate and strengthened program integrity at the Department of Veteran’s Affairs.

This is evident in the next table which is often referred to as “the table of truth”. The first row show the budget deficit forecasts from back in the March Budget. The next row shows “parameter changes”, ie changes which occur in current programs and tax collections without changing any policies. This is positive because tax revenue upgrades (particularly from higher commodity prices) more than offset higher payments under existing programs (with eg higher-than-expected payments to veterans and defence force super and an extra $6.3bn for disaster relief). Overall, “parameter changes” served to reduce the budget deficit by $7.6bn over four years with most of that occurring this financial year.

While the next line shows that there has been some “new policy stimulus” this year and next, it has been offset by budget savings over the four years as a whole such that new policy measures reduced the deficit by $1.1bn over the four years as a whole.

The net effect of the upgraded tax revenue and policy savings set against higher spending commitments means that the budget deficit profile is now slightly lower over the next four years. See the next chart. And because the budget numbers are better for 2024-25 net debt is expected to be lower than previously expected but is still projected to worsen to $755bn, or 22.6% of GDP, by June 2029. Gross debt is now not expected to go through $1 trillion until 2026-27.

A cynic might also note that the Government’s projections for the deficit and spending bounce higher in 2029-30, which is the first year outside of the forward estimates at which point the budget deficit profile then looks worse again than in the March Budget!

Source: Australian Treasury, AMP

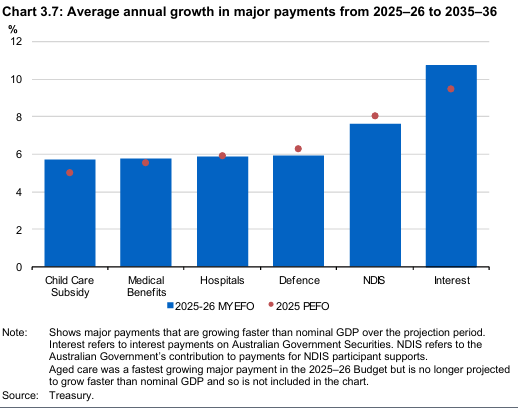

The key structural spending pressures on the budget are unchanged and are – rising interest costs with the latest surge in bond yields on the back of higher inflation and a less favourable cash rate outlook not helping and unlikely to be fully reflected in the revised budget numbers, the NDIS, defence, health and childcare.

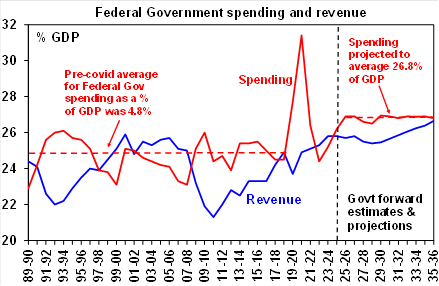

As a result, the picture for Federal Government spending and revenue is little changed. Spending as a share of GDP over the decade ahead is still expected to average nearly 27% of GDP, which is well up on the 24.8% of GDP that prevailed pre-covid. Note that the dip in the spending share in 2026-27 and 2027-28 shown in the next chart reflects optimistically low levels of real spending growth of just 0.3% in 2026-27 and 1.2% in 2027-28. But past experience tells us that once we get there the spending growth numbers will be revised up. This is particularly likely to be the case in 2027-28 which will likely include the next Federal election.

Source: Australian Treasury, AMP

Assessment

The good news remains that Australia’s budget deficits running around or just above 1% of GDP and gross general government debt of around 51% of GDP are small compared to many comparable countries. For example, gross general government debt averages around 110% across advanced economies and in the US its around 125%. And at least the mid-year update saw a slight reduction in the outlook for budget deficits.

However, there are five key problems with the Government’s fiscal strategy.

Structural deficits – the Government is continuing to lock in structural budget deficits. No money is being put aside in the form of budget surpluses for a rainy day, like a global recession, and budget balance is still a decade away at best.

Structural spending on temporary revenue – spending commitments have been ramped up over the last three years on possibly temporary revenue windfalls which have amounted to $300bn or more since the October 2022 Budget. While this budget update saved slightly more of the revenue upgrade, previous budget updates had been spending most of it. This leaves the budget vulnerable to a reversal of the revenue windfalls.

Reliance on bracket creep to boost revenue and return the budget to balance – however, spending growth estimates look implausibly low at 0.3% pa and 1.2% pa for the next two years (particularly in 2027-28 when another election will be due) but more importantly the reliance on bracket creep means an ever-rising income tax burden on Millennials and Gen Z which is unfair and unrealistic. Politicians will eventually want to give some back as “tax cuts” and then how did we get back to a surplus?

Off budget spending – a growing concern is the widening gap between the underlying cash balance (which is the difference between budget revenue and payments) and the headline cash balance (which allows for net cash flows from investments). During the time of big privatisations in the 1990s, the focus shifted to the former as the latter was making the budget look better than it really was. But in recent times increasing amounts of “off-Budget” spending have been excluded from the underlying cash balance on the grounds that they are investments (eg the NBN, various investment vehicles relating to things like housing and manufacturing and changes to student debt). The problem is that this is resulting in a widening negative gap between the headline and underlying balances. Unfortunately, some of these expenses are not necessarily wise investments and may have to be written down in value – but they still add to Federal debt. In the interest of budget honesty perhaps the focus should shift back to the headline cash balance.

Source: Australian Treasury, AMP

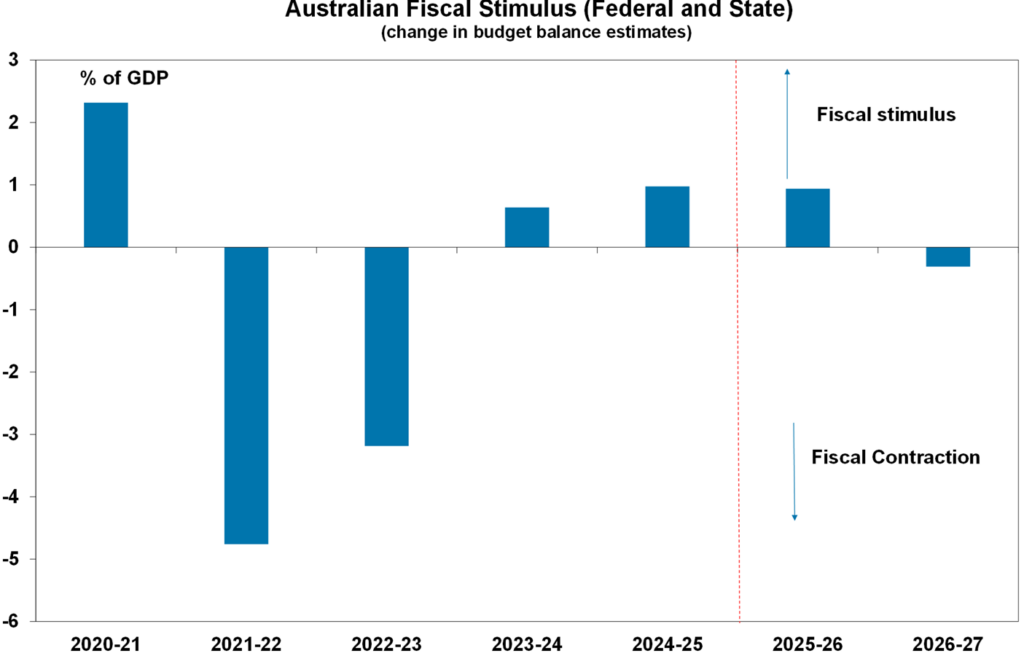

Excessive public spending – Federal Government spending as a share of GDP is settling well above levels seen pre pandemic and leading to total public final demand running around a record share of GDP of around 28%. This is likely a key driver of lower productivity seen in recent years (as the public sector tends to be less productive than the private sector) which in turn is depressing living standards. The continued strength in public spending is also adding to capacity constraints in the economy which is being made worse by the swing into budget deficits providing nearly another 1% of GDP of fiscal stimulus being pumped into the economy. This boost to demand at a time when private sector spending is trying to recover means higher than otherwise inflation as the public sector is competing with the private sector for resources and driving prices up. All of which is making the RBA’s job in keeping inflation down harder and will if the RBA has to raise rates next year put more pressure on the private sector – particularly Australian households – to keep a lid on their spending. In other words, ongoing high public sector spending means higher than interest rates, and mortgage rates for households, than would otherwise be the case.

Source: Australian Treasury, state budgets, AMP

How the budget strategy could be improved

There are four key things that could be done to improve the fiscal strategy:

First, adopt a set of quantitative fiscal rules that can be tracked and the Government assessed against. These were common under Australian governments since the “budget trilogy” imposed by Treasurer Paul Keating in the mid-1980s. Ideally now it should contain commitments to cap real spending growth, cap tax revenue as a share of GDP and bring the deficit back to balance in say three years.

Second, greater means testing and co-payments should be introduced into the provision of public services to ensure they are targeted for those who really need them.

Third, Government spending should be subject to an independent audit to ensure its achieving value for taxpayers’ dollars.

Finally, tax reform is a whole separate issue but at the very least the tax thresholds should be indexed to the inflation target (2.5%) to ensure we don’t get lulled into a false sense of security relying on bracket creep to bring the deficit down and imposing an ever higher tax burden on workers.

With the next Federal election more than two years away, the Government having substantial political capital flowing from its huge parliamentary majority post the last election, growth in the private sector starting to recover and capacity constraints coming to the fore again with renewed inflationary pressures now is the ideal time for the Government to be biting the bullet and getting government spending back down to pre-pandemic levels. It did a little bit of this in the mid-year budget update – but nowhere near enough.

Ends