by David Elms – Head of Diversified Alternatives | Portfolio Manager

2022, to date, has been a year of seismic change at every level, with profound consequences for everyone, not just financial markets. The risk of significant geopolitical escalation remains, whether that is between Russia and the western world or, more recently, China and the West over Taiwan. These are things that could be game changers for the world.

The inflation/interest rates conundrum

The ramp-up in interest rates this year, in response to inflation, is a huge change for investors long-since used to what has been a very benign environment. This has posed questions about what happens in a modern market environment, with modern investment techniques, where the pricing of risk is changing.

A good example is the role of bonds in a portfolio. The correlation between bonds and equities has been persistently negative since the late 1990s, with some exceptions. A traditional bond/equity portfolio has benefited from the natural risk offset created by that negative correlation. Bond yields were also at high enough levels that there was the potential for yields to go down in a crisis, creating capital gains that could stabilise a portfolio.

But in a low-yield environment, in inflationary times, the correlation between bond and equity prices is less certain, and your typical 60/40 portfolio is not going to look, or behave, in the same way as it has before. The question now is if we believe we are in a regime where inflation is likely to remain persistently above 2% in the economies we are focused on, the point at which the correlation between bonds and equities seems to become less certain, potentially flipping from negative (ie. diversifying) to positive (ie. correlative).

On the balance of probabilities, this scenario seems likely. The question then turns to how investors can potentially stabilise that ‘balanced’ portfolio. In our view, the current environment calls for broader thinking. This is where alternatives come into the picture.

Don’t look to the past for clues

If we go back to the 1970s, the most recent period that we had substantial increases in inflation, the market was a different place. The market participants were different, the role of retail was different, and the scale of hedge funds was very much smaller. It is a risky game to assume that market behaviour will follow the same path. But there are some strategies that we expect could still do well.

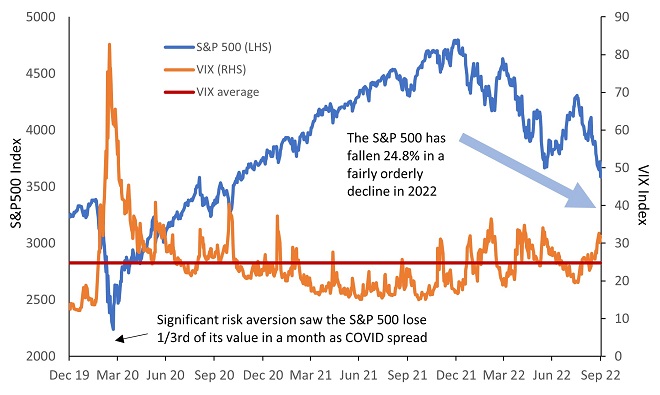

Trend-following strategies, for example, might offer part of the solution for investors. The US market was down almost 25% year-to-date to the end of September 2022. But while volatility has crept up, it has been a relatively orderly decline thus far, without the very sharp moves – up and down – that were present during the COVID crisis in 2020 (Exhibit 1). When you see a stable trend, you would expect trend-following strategies to stand out. Another attraction of trend-following strategies is that they are scalable and can be built at a reasonable cost for fee-sensitive investors. These are the characteristics that large-scale investors need.

EXHIBIT 1: MARKET FALLS IN 2022 HAVE NOT CORRESPONDED WITH HIGHER UNCERTAINTY

Source: Janus Henderson Investors, Refinitiv Datastream, 31 December 2019 to 30 September 2022. Past performance does not predict future returns. Note: The VIX Index is a real-time market index used as an indicator of the market’s expectations for volatility in the S&P 500 Index over the coming 30 days.

But trend following requires the right kind of market. If we go back to 2020, we saw the S&P500 Index lose a third of its value between 19 February and 23 March. Sentiment flipped suddenly and dramatically as the rapid spread and severity of COVID became apparent. In a similar environment, trend following could tend to struggle, given how fast asset prices moved.

“It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.” (various)

In crisis periods, assets become correlated. In other words, diversification works in normal market environments, when arguably it is not needed, but tends to fail in a crisis (with correlations trending to one) when its benefits are most needed. This is not necessarily because portfolio construction is broken, but rather because you tend to see herding from investors during periods of acute uncertainty. This herding behaviour is an intended consequence of modern risk management practices, which have a general focus on adjusting portfolio exposures in response to market volatility, and which have become prevalent over the past three decades, dating back to JP Morgan’s commercial launch of RiskMetrics in 1992.

For institutions such as banks, hedge funds and traditional asset managers, if the volatility of a portfolio is unacceptable, de-levering – selling long positions and covering short positions – is the common response. However, de-levering pushes prices down which can deepen the crisis. Volatility consequently goes up, which leads to more de-levering. This is known as a ‘value-at-risk’ spiral. In that environment, it is easy to see why diversification fails, because most investors are forced to liquidate by their risk management disciplines. What works at an individual level as a risk management tool has a tendency to exacerbate risk flare-ups when widely deployed across the industry.

When diversification doesn’t work, what do you do?

What matters for those game changing moments is to have a liquid portfolio with a range of different strategies offering uncorrelated approaches and incorporating different forms of crisis alpha, such as volatility strategies, trend-following and discretionary macro. So-called ‘protection’ strategies offering reverse polarity with regards to risk can be helpful when diversification is breaking down.

The counterargument is that paying for that peace of mind can create a drag on return over time, but we would argue that the shape of returns is as important as their simple magnitude. This shape can be vital to investors who are looking to retire, or those who can’t afford to risk a significant loss of value. It does not work for everyone. You need to consider what assets a client holds, what their liabilities are, and what their objectives are. But, given the scale of change and uncertainty markets have experienced over past few years, you have to ask yourself if you can afford to focus solely on return maximisation, without considering the benefits of risk management and protection strategies.