by Robert Almeida – Global Investment Strategist, Portfolio Manager

In brief

- In recent decades, negative correlations between stocks and bonds have been a tailwind for asset allocators, but negative correlations have been the historical exception, not the rule.

- Investors may need to change their expectations given the potential for a reversal of negative real interest rates and a shift in the stock-bond correlation.

- We think the combination of multiple asset managers in the same asset class and differentiated alpha levers can improve portfolio efficiency.

In 2013 the Boston area was paralyzed by three big snowstorms on consecutive Saturdays. On the next Saturday, my six-year-old daughter Sarah asked me, “What time will the snowstorm start?” Like Sarah, every investor at some point confuses correlation with causality, and this can lead to unwelcome financial outcomes. However, ignoring long-term relationships, whether the cause is easily identifiable or not, can upset an otherwise-well-thought-out investment plan.

Negative stock-bond correlation was abnormal

Many market participants consider the equity-like bond returns of the past 30 years abnormal. Equally abnormal were the stratospheric risk-adjusted returns achieved by balanced and multisector portfolios over that period. While the absolute strength of bond returns and below-average price volatility largely explain this, another, overlooked, cause was the negative correlation between equities and bonds. That, too, is an anomaly that we should expect to end.

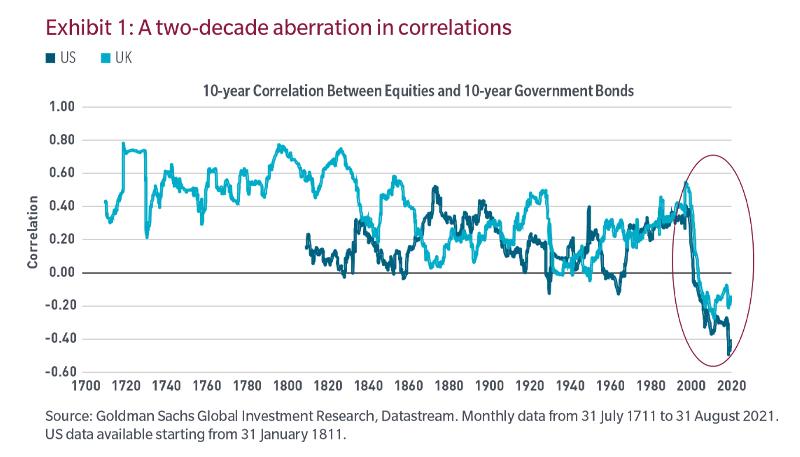

Exhibit 1 tracks the centuries-old relationship between stocks and bonds in the United Kingdom and the United States. Until the past few decades, the correlation was consistently positive, which makes sense because investing, whether in stocks or bonds or in private or public markets, means foregoing consumption now in order to provide capital for a project that should then compensate investors both for the time their money is tied up and the investment’s inherent risks. While this an oversimplification, in a sense there is in fact only one asset class: the volatility of cash flows.

For example, the value of a US Treasury bond that will mature in seven years is a function of its future coupon payments compared to other available investment opportunities. If inflation is rising, driving the coupon rates of on-the-run Treasury issues higher, then our seven-year bond is worth less by comparison and its cash flows fall short of prevailing market rates. The same holds true for equities as their values are also dependent on future cash flows. Through this lens, all financial assets are ultimately tied to a future cash flow stream, and this helps explain why there is a positive correlation among financial assets over long periods.

What happened and what could change?

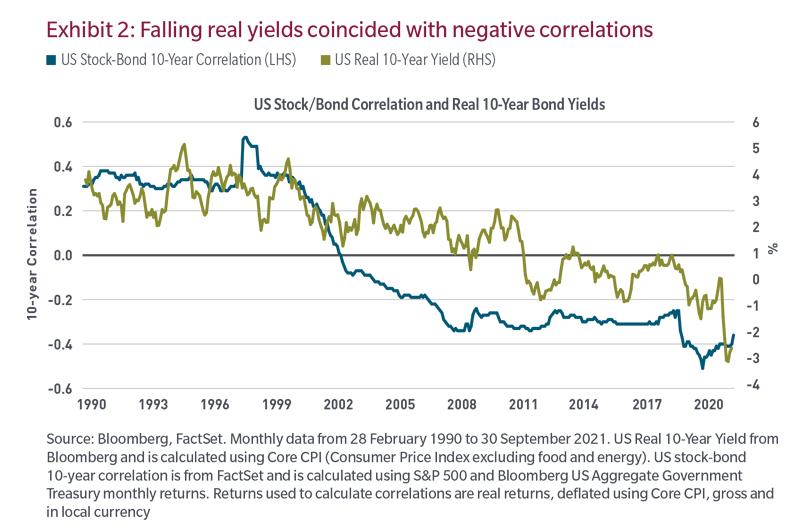

Exhibit 2 shows the relationship between the stock/bond correlation and real rates during the same period. As central bank intervention grew and real yields fell, stocks and bonds became increasingly negatively correlated.

Perhaps, like my daughter, I’m mistakenly inferring causality from coincidences. However, we know that capitalism requires a hurdle rate. Investors rely on undisturbed market signals to price risk. Without them, markets can’t perform their societal function, which is to allocate capital resources efficiently. The result is financial market abnormalities such as the ones we’ve witnessed in recent years. In our view, as the hurdle rate rises, which we expect it to, so too should risk premia, volatility and financial asset correlations.

Rethinking portfolio construction

With the potential for shifting correlations and a normalization of real interest rates in the coming years, perhaps it’s time to take a fresh look at portfolio construction. When something is abundant, its value falls. When it isn’t, its value rises. Financial returns have been abundant for years (see “Are Yesterday’s Tailwinds Tomorrow’s Headwinds?”), and this helps explain why lower cost market beta took significant share from actively managed portfolios. In our view, if market returns become scarce, the opposite should hold true, as there’s a cyclicality to passive and active performance. And while alpha may offer the desired financial return in a potentially underwhelming market environment, it could also deliver scarce diversification for portfolios.

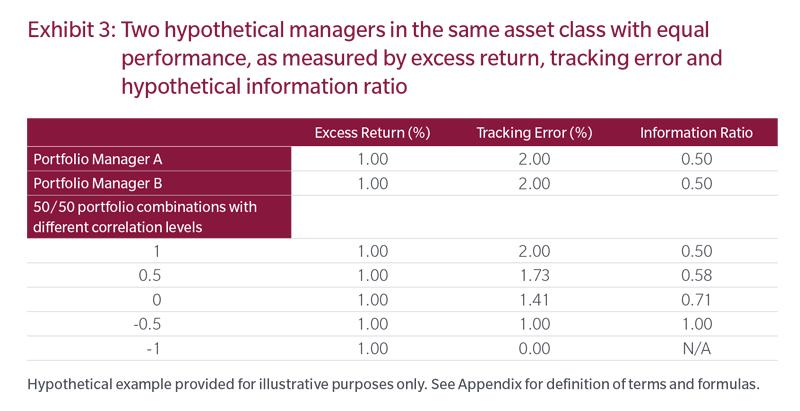

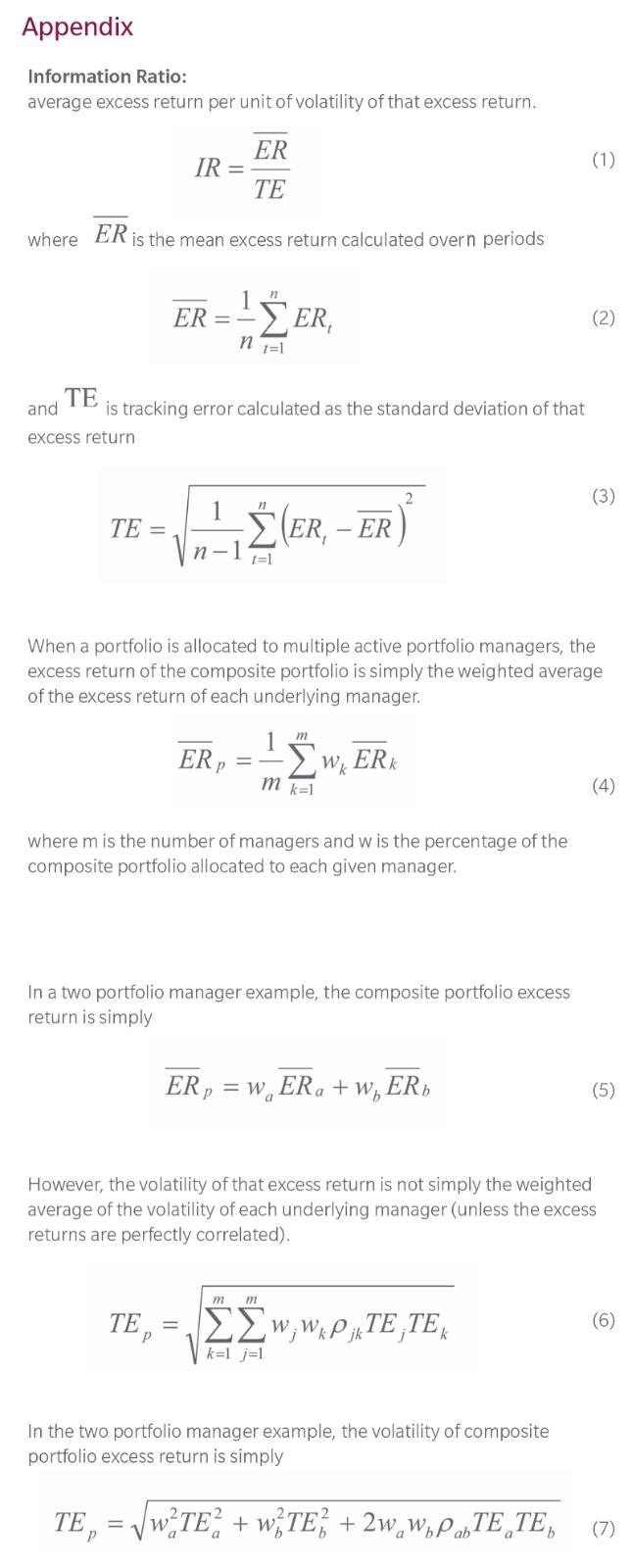

Investors tend to think of diversification in absolute return space. However, it exists in relative return space too. In the same way that two less-than-perfectly correlated assets, such as stocks and bonds, can be combined to improve absolute efficiency, two active managers within the same asset class, such as investment grade credit, can be combined to potentially improve the risk-adjusted return or information ratio.

Within an asset class, when a portfolio is allocated to multiple active managers that have different alpha levers, portfolio efficiencies can be achieved. Exhibit 3 illustrates this by looking at two hypothetical active fixed income managers. While there is no benefit when the correlation of their active returns is high, the information ratio improves as correlation falls.

Conclusion

Research shows that people generally remember only about 10% to 20% of what they read and hear but recall roughly 80% to 90% of what they’ve experienced. Given the experience of the last 30 years, stocks and bonds moving in the same direction again will run counter to the expectations of most investors.

Going forward, I think discretionary portfolios with differentiated alpha streams within like-for-like asset classes may not only help fill some of the void created by the likelihood of lower returns in the future, but also help manage the risk of a return to positive correlations.

Bloomberg Index Services Limited. BLOOMBERG® is a trademark and service mark of Bloomberg Finance L.P. and its affiliates (collectively “Bloomberg”). Bloomberg or Bloomberg’s licensors own all proprietary rights in the Bloomberg Indices. Bloomberg neither approves or endorses this material, or guarantees the accuracy or completeness of any information herein, or makes any warranty, express or implied, as to the results to be obtained therefrom and, to the maximum extent allowed by law, neither shall have any liability or responsibility for injury or damages arising in connection therewith.

“Standard & Poor’s®” and “S&P®” are registered trademarks of Standard & Poor’s Financial Services LLC (“S&P”) and Dow Jones is a registered trademark of Dow Jones Trademark Holdings LLC (“Dow Jones”) and have been licensed for use by S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC and sublicensed for certain purposes by Massachusetts Financial Services Company (“MFS”). The S&P 500® is a product of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, and has been licensed for use by MFS. MFS’s product(s) is not sponsored, endorsed, sold or promoted by S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, Dow Jones, S&P, or their respective affiliates, and neither S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, Dow Jones, S&P, their respective affiliates make any representation regarding the advisability of investing in such product(s).