by Greg Wilensky – Head of U.S. Fixed Income and Michael Keough – Portfolio Manager.

Computers in the future may weigh no more than 1.5 tons.

– Popular Mechanics magazine, 1949

Popular Mechanics was absolutely right. They correctly – perhaps brilliantly, considering the silicon chip wasn’t invented for another decade – predicted that the size and weight of computers would fall in the future. But the extent to which they were wrong about the magnitude of that change is breathtaking. No matter how right you may be on the “what,” there is so much room to be wrong on the “how.” To put it in terms that many investors are thinking about today, no matter how confident you may be that interest rates will rise as the U.S. economy recovers, there is still much you can be wrong about.

Had an investor correctly predicted a global pandemic would erupt in the first quarter of 2020, we can imagine they would have sold stocks and bought government bonds before it started. But one could argue that without a detailed map of the markets’ exact paths, the knowledge that a pandemic was coming would have been less valuable than you might think. When would the investor have decided to reverse their more cautious position? What is the probability they covered their position a little or a lot, too early or too late and thus lost as much money in late March as they made in early March?

Correctly predicting the general direction of financial markets far into the future is certainly helpful but gauging the timing and magnitude of the moves is just as important and often more difficult. We suspect few, if any, bond managers predicted the shock of COVID-19 even in January 2020, but many experienced portfolio managers were able to not only navigate the volatility, but also find opportunities to add value for their clients, whether through lower volatility relative to their benchmark, higher returns, or both. Indeed, the task of portfolio management is, in our view, to build portfolios that are designed to perform well given both our predictions and the potential uncertainty that surrounds them and the world we live in.

We anticipate rates will continue to rise

In general terms, we believe the U.S. economy will continue to recover and the labor market will strengthen enough to push both inflation and interest rates higher. But predicting the magnitude and timing of these moves is very difficult. And, even if our prediction for the eventual peak of interest rates is highly accurate, we think portfolios need to manage the downside risk of less bullish outcomes as we navigate the economic reopening and concurrent responses from central banks.

The first quarter of this year saw a decidedly disorderly rise in government bond yields, but – in hindsight – it is not surprising. After nearly a year of fear and concern about the breadth and depth of the pandemic, the market abruptly repriced. We expect even the investors who called for rates to rise probably got the magnitude and/or the velocity of that move wrong. But, as we look to the future, we do not anticipate the degree of volatility we saw in the first quarter will persist.

The value of humility

As good as any portfolio manager might be, surprises will happen. That is not to say that some managers aren’t better than others at predicting the direction of certain sectors, industries, or even companies. But humility is important. As University of Pennsylvania professor Philip Tetlock described in his 2006 book Expert Political Judgement, “experts” are often actually worse at predicting outcomes within their specialty than ordinary people. At the risk of oversimplifying his book-length argument, the core of the problem is overconfidence.

The probability of a shock in any given year is largely independent of whether a shock has recently occurred … and best assumed to be a constant, if small, possibility.

The fact that a major shock like COVID-19 recently happened to the market may make it seem less likely that something of that magnitude will happen again soon. But the probability of a shock in any given year is largely independent of whether a shock has recently occurred. The probability that markets will experience a shock is best assumed to be a constant, if small, possibility. Given that these low-probability events (sometimes called “black swans” given their rarity) can have an outsized impact on returns, a humble investor who recognizes the challenge of forecasting the next black swan should, in our view, prudently build portfolios that help keep the downside risk from one of these events within acceptable limits.

The value of diversity

To paraphrase the old saying, we don’t believe you should put all your eggs into one forecast. A portfolio should be filled not just with a diversity of sectors and securities, but a diversity of risks. The math backs this up. Even if the probability of being right in any one forecast is high, the probability of a portfolio performing well over time will be higher if there are more forecasts that are as independent of each other as possible. To give you a sense of the math, if you allocated your portfolio’s risk across 10 different market forecasts that were reasonably uncorrelated to each other, each having a good chance of being right, your portfolio would likely result in a better risk-adjusted return than if you had all your risk allocated to one forecast that had a higher chance of being right.

Even if you are ultimately right about your forecast though, maintaining the position can be tough if the market doesn’t agree with you. The celebrated economist John Maynard Keynes summed this point up well in his quip that “the market can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent.” And, one could be right about U.S. economic growth recovering strongly, but wrong about its impact on U.S. interest rates. For example, the extent the U.S. outperforms the global economy, global weakness could both temper inflationary pressures and increase demand for U.S. fixed income instruments from foreign buyers, keeping rates suppressed.

Managing interest rate risk is one valuable, and important, tool in portfolio positioning, but we recommend incorporating humility when budgeting the amount of risk allocated to positioning based on one’s interest rate expectations, so as not to place too much confidence in the accuracy of just one forecast. Additionally, the alignment of expectations between clients and investors is of the utmost importance. For example, the amount of risk budgeted to a rate forecast should vary based on whether a fixed income allocation is meant to provide a hedge to risks across a broader investment portfolio. Substantially reducing the interest rate sensitivity of a fixed income portfolio could inappropriately increase the downside risk for an investor with large allocations to equities should we experience another economic shock. On the other hand, if an investor’s allocation to riskier assets such as equities or high-yield corporates has been declining, the need for that hedge has likely decreased and the fixed income allocation could benefit from reducing duration in expectation of higher interest rates.

A portfolio should be filled not just with a diversity of sectors and securities, but a diversity of risks.

Thinking about excess returns

Rate forecasts aside, we believe investors should always be looking to investments with the potential to outperform similar duration U.S. Treasuries. The technical term for this is “excess return” insofar as these investments generate a return in excess of the return generated by Treasuries.

Corporate bonds, for example, pay a yield higher than Treasuries. As long as the spread (the difference in those yields) remains constant, owning corporate bonds will result in an excess return over Treasuries because of this spread. Of course the spreads can widen, which hurts the excess return, or tighten, which improves the excess return. Whether the spread expands or contracts can be correlated to the direction of interest rates but it can also be influenced by other factors, such as the conditions and outlook for the economy as a whole, a particular industry or a specific company.

Ultimately, both corporate bonds and the wide range of securitized assets available in today’s bond market typically provide higher yields than U.S. Treasuries while providing some diversification. Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS) and floating-rate investments like many commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS) and collateralized loan obligations (CLOs), can provide even more diverse profiles of interest rate risk and income. Our outlook for a strong economy and improving fundamentals leads us to believe that such opportunities should provide some spread over Treasuries, creating an additional yield cushion that can help shelter capital against rising interest rates.

Losing when your rate forecast is right – the shortcomings of standard duration measures

When investors consider the interest-rate sensitivity of their fixed income holdings, we think it is critical that they consider the limitations of the standard mathematical estimation of its duration. While there is a general understanding that non-Treasury securities exhibit less interest rate sensitivity than Treasury securities with the same duration, many investors do not systematically account for this in their investment decisions. The standard calculation for duration provides the expected return for a change in the investment’s yield, but this mathematical calculation can be unhelpfully simplistic.

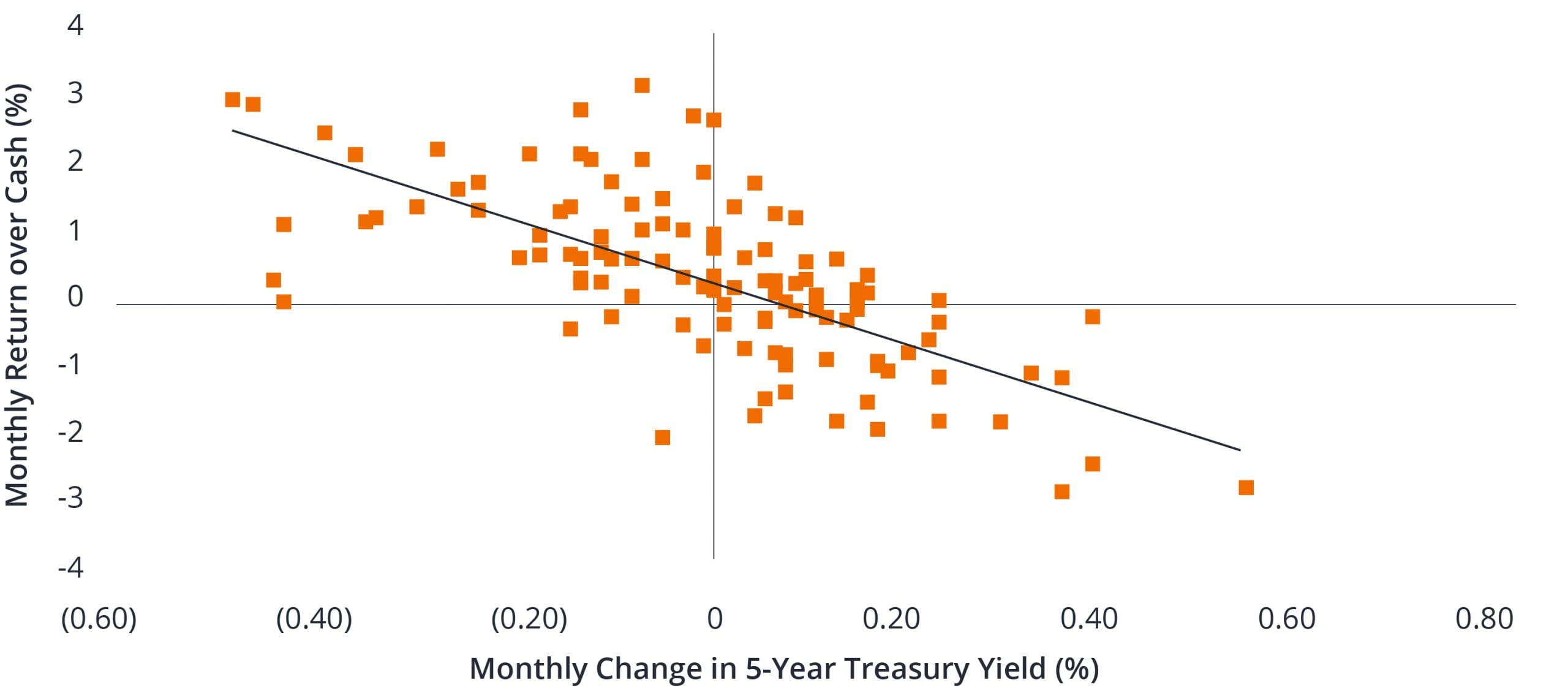

Consider Figure 1 below, which shows the historical relationship between changes in the 5-year U.S. Treasury bond yield and the return of the investment-grade corporate bond index. When Treasury yields rise, corporate bond returns have tended to fall. However, the sensitivity of the relationship does not match the mathematical duration of the corporate bond index. Instead, it has empirically behaved like it has a significantly lower duration. The average mathematical duration of the corporate bond index over the period shown was near 7.4 years. However, the slope of the line graphed shows the sensitivity to be closer to 4.7 years – a significant difference, with potentially significant effects on returns.1

Figure 1: U.S. Treasury yield changes versus corporate bond returns

Source: Bloomberg, Janus Henderson, as of 31 March 2021. Corporate Bond returns are represented by the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Corporate Bond Index, which measures the U.S. dollar-denominated, investment-grade, fixed-rate corporate bond market.

Even if an investor properly forecasts where 10-year Treasury yields will go, knowing how a portfolio will behave empirically is crucial to delivering the intended outcomes. We believe that taking a systematic approach to estimating and using “empirical durations” will lead to better risk-adjusted performance. Failure to do so could lead to underperformance even if your interest rate forecast is accurate.

The logical conclusion

Volatility in markets is not a bad thing. It creates opportunities for active managers. The volatility in 2020, coupled with the interventions by the U.S. Federal Reserve and historic fiscal stimulus, created opportunities for managers to express strong convictions. There is, in our view, nothing wrong with feeling confident about a forecast. The trick is to make sure the resulting positions are sized appropriately within an overall risk budget. Humility, and diversity, matter.

Just as we believe in the importance of diversifying risks and holdings within core fixed income portfolios, we believe investors should be mindful of that same diversity across their overall portfolio of investments. The ultimate mix is, ideally, a result of individual goals, risk tolerance and investment views. Given a strong conviction that rates will rise sharply, investors may consider either reducing overall fixed income exposure or making adjustments within fixed income allocations to increase exposure to strategies with lower interest rate sensitivity, including shorter-duration or higher-income strategies. The key point to remember is in markets with a wide range of outcomes, allocating too much of your risk budget to a single forecast, such as the direction of interest rates, can result in increased risks. A little humility and diversification in portfolio construction can go a long way.

ENDNOTES

1Source: Janus Henderson Investors, as of 31 March 2021. In the regression equation y=mx+b, m is the slope of the line, in this case, showing the relationship between changes in Treasury yields and corporate bonds returns. The equation for the regression graphed is y=-4.7x+0.36. Thus, the corporate bonds returns have exhibited a duration of 4.7 years.