Australians are lucky to have arguably the most developed pension system in the world. An important aspect to understand is what caused this choice and what are the trade-offs for this choice.

Now before I go on, I want to go on record and say that I unequivocally believe that choice is good. The more choice one can have, the better of you are, all else equal. In Australia, we have low-cost industry/retail funds, we have Small APRA Funds, we have SMSFs, we have “wrap” platforms and more. If you rewind 20 years, the environment looks vastly different. Before we start focussing on the how, we need to start with the why.

Historical Pension Funds

Nearly all pension systems around the globe started off with the bulk of, if not all, pension assets in what are known as ‘defined benefit’ funds. In these DB funds, the crème de la crème was the lifetime indexed pension DBs where a member received an indexed income stream every year from retirement until they passed away. Assuming of course that the pension fund could afford the payments.

The method of calculation was typically some form of equation that factored in; years of service and income level among other things. The key difference to the current system being that the fund manager bears all the risk. Whether the market rises or falls, the member theoretically still receives the same level of income.

People’s entire lives were often driven by which pension fund they wanted to end up in. Industries and employers were selected based on the quality of the pension they offered, and in many cases, employees committed themselves to employers for life in order to maximise their retirement benefits.

A very different equation to today’s transient job market.

Current Day Pension Funds

The current system in Australia is built almost entirely around ‘defined contribution’ funds. Where your available balance is defined by how much you have contributed, plus or minus investment returns. In other words, you bear ALL of the risk. If you start one year with $1M and the market drops by 10% and you draw out $50k, you start year 2 with $850k.

Why did it change?

Logically, the DB environment cannot exist today like it did throughout history. The main reason being changes to life expectancy. In today’s world your average person will live a very long retirement by historical standards. As a result, a pension fund manager simply cannot guarantee income payments for a retirement that may well last 30+ years. Back when median life expectancy was 70, the game was a lot easier.

The crux of the matter is that, the ratio of time spent in the workforce filling up the pool to time drawing down on the pool, is now dangerously in favour of the latter. Even today we are seeing pension funds who pay out these lifetime pensions, making reductions to pension amounts due to funding issues within the pool.

This, understandably, can cause major stress to retirees as well as changes to lifestyle that were completely unforeseeable until they happened. It is not dissimilar to running a race based on where you have been told the finish line is, only to have the finish line moved by the time you get there.

What are the key implications of this change?

When the risk transfer happened, we started to see a massive change in the way pension money was invested. We saw a movement toward liquidity and an openness to increased risk. A key reason for this search, is that inflation and interest rates are much, much lower than they were in the 70s and 80s making attractive returns harder to achieve. Back in 1981 you could buy a 30-year U.S. Bond with a coupon rate at 15% pa, the same asset today would provide you a yield of 2.25% pa. What this means is that investment managers have to seek out riskier assets to provide retirement funding for investors. Investing is getting harder and harder.

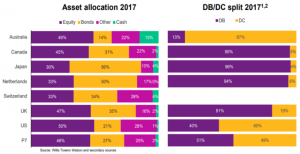

As at 2017, Australia had the second highest amount of pension assets (in percentage terms) in listed equities at 49%. First place goes to the US with 50%.

The below table highlights this:

Risk is neither bad nor good, it just is. What investors need to keep in mind is that they now have all of this choice and flexibility, and they need to determine how best to exercise that choice with respect to their risk profile, retirement needs and investment preferences.

Aside from increased life expectancy, the lower risk nature of investment selection in a DB fund has also caused funding issues. With more assets in lower risk assets such as bonds, it is a fair assumption to expect the long-term annualised returns to be higher in a DC fund. This leaves an investor with one of two choices; take on an appropriately increased level of risk OR accept that they will also have funding issues and know that they will certainly live a reduced level of lifestyle in retirement.

There is no right or wrong way to approach this choice, investment decisions for the 99% will be, and always have been, about concessions. The question we all have to answer is, what am I willing to concede on first.